Communicate

Alumni Stories

Alumni Stories

Finding my inspiration to write | 延續父親寫作夢

Yan Chi-ming 甄子明BEng 1976; DipManStud 1983; MBA 1985

By Yan Chi-ming

When I was a little boy, I was surrounded by bookshelves and books. My father was a professional writer and he wrote Kung Fu novels, which were very hot in the 60s. He loved Kung Fu novels himself, so he had a stock of them written by other famous writers, especially Jin Yong 金庸. My first books were Kung Fu novels by Jin Yong and my father. I was 8.

Since then, I have never stopped reading.

At around 12, I began to try my hand at writing short stories and very “simple but naïve” poems for newspapers.

Reading was fun. When I was in primary school, my books were all Chinese. There were all kinds of different books, from scientific books for children, to Kung Fu novels, to novels by Qiong Yao, which were meant to be for girls. I loved adventure books translated into Chinese. I knew the names of Sherlock Holmes, Mark Twain, Jack London, and Jules Verne at around 11 or 12. I also read Chinese classics systematically, including “the Three Kingdoms”, “The Water Margin”, and works by modern Chinese writers, such as Mao Dun 矛盾、 Lao She 老舍、 Ba Jin 巴金、 Lu Xun 魯迅、 Bingxin 冰心.

My interest in history was inspired at the age of 8 by Kung Fu novels. Most of my knowledge in Chinese history was learned this way, not from school. Together with the history I learned, these novels helped me to develop my sense of being Chinese.

One of the issues Kung Fu novel writers had was the treatment of the Qing dynasty. Should it be treated as a Chinese dynasty or a foreign power ruling over Han China? This conflict was never satisfactorily resolved, whether in real life, or in the interpretation of history, or by novel writers. I was, of course, confused at that time. This interesting dilemma inspired me to include an element of nationalism in my novel “1849 Sun Rise and Sunset”.

When I went to University, I wanted to have fun. I sought the best fun life at university, and found myself living in University Hall, which was to become the core of my life for the next three years. The experience of staying there is lifelong. Fun was a double-edged sword. While those three years were really fun and became part of me, I rarely read or wrote. If student life was so much fun, my hobbies had to wait.

Surprisingly, university life did not give me inspiration to write. Fellow students discussed Jin Yong’s novels, but that was more a social pursuit than an intellectual one. Politics was the order of the day in the 70s. While it inspired a lot of students, many of whom became leaders later on, it failed to inspire me or expand on my understanding of history.

The first few years after graduation were another golden period for my passion in literature and writing. I wrote a lot, but it was not planned or organised. I tried to do translation, and started by trying my hand on one of Jack London’s novels. I also turned to writing a high school science book on water. Both projects failed.

I went to the LSE in London to study economics at the age of 32.

This decision led to an unintended consequence. During my two years in London, I had all the time to read all the books I wanted. Although my degree was in economics, I also attended classes in social science and history, and I loved them. I finished reading about the basic history of all non-Chinese civilisations, from the Greeks and the Romans, to the Mayas and the Incas, to the history of the English-speaking peoples (by Winston Churchill) and European history. I attended most of the classes in sociology and history of social science for undergraduates, and followed the reading lists on classics by authors such as Socrates, Plato, David Hume, Tocqueville, and Saint-Simon. With my economics courses and reading, I thought I had completed a basic grasp of Western civilisation: philosophy, history and economics, comparable to the PPE course offered by Oxford. Now that is what I consider a real education.

Unfortunately I did not write in those two years, just absorbed knowledge like a sponge. With a baby to look after as well, I did not have the energy to do any literary work apart from reading.

For the next 25 years, after I returned to Hong Kong in 1989, I was busy with full-time work, both in Hong Kong and China.

I have learned a lot about business and China in those years, since a major portion of my work concerns China business. Coupled with my exposure to Chinese literature and history when I was younger, the new experience allowed me to understand China in greater depth and detail. China is no longer something in the past, or in a book, but it is real life, real people. I have spent years living in different cities in China, and have travelled to others. My approach is to combine both the literary and historical knowledge with present real-life activities in order to get the whole picture. That is to say, when I see and feel present day China, I always try to ask myself the reasons why these things happen, and go back to my knowledge base in history or somewhere else to find answers.

On the other hand, firsthand knowledge in the present helps us understand the past. I believe in my eyes, ears and brain. If I can figure out why things are like they are, based on present observations, it is likely that people in the past would have behaved similarly. Human nature would not have changed much in China’s 4,000 years of history. This is a very interesting interaction, and becomes the basic philosophy for my first novel “1849”.

A Chinese writer in historical novels gave me opportunities to test this hypothesis, and greatly inspired me. He is Eryue He 二月河 , the author of a famous trio: Kangxi Emperor 《康熙大帝》, Yongzheng Emperor 《雍正皇帝》and Qianlong Emperor《乾隆皇帝》. Stories and characters in his novels are so vivid and real. How can that be? No one knows what really happened in the past! When I applied my philosophy, I realised the gambit. He knows and understands present-day China. He just applies this understanding to the past, assuming that people in the past would act in similar ways. That is the way to write historical novels.

In the new millennium, I thought about pursuing an advanced research degree in history, but then the modern approach to research is to specialise in a narrow area, That is completely opposite to my philosophy, which is to draw meaningful conclusions using facts and logic based on inter-disciplinary references. I decided to drop this idea, and concentrate my efforts in my own way, which will be more efficient.

The idea of writing historical novels began to take shape.

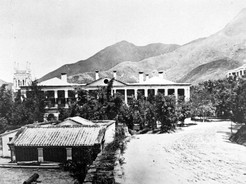

There is another important issue: Hong Kong. When I was a little boy, Hong Kong and China seemed to be located on two different planets. China relied on Hong Kong for a lot of things, both materialistic and as a window to the world. Even as a teenager I understood some of the importance of Hong Kong to China. I often pondered why.

Hong Kong was unique, complicated, impossible to understand, but fascinating.

My interest in Hong Kong has never died.

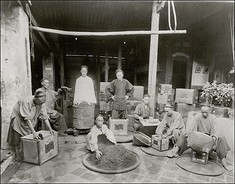

These passions and interests drove me to write my novel “1849”. I wanted to paint a different (and possibly untold) picture of China and Britain after the Opium War, the story of which has seldom been revealed. I also wanted to tell the true story of Hong Kong, and its interaction with Britain and China. I believe Hong Kong’s unique influence on China has been underestimated by politicians, and somewhat neglected by historians. I have tried my best to retell stories of those few years from my own perspective.

Episode

After finishing the novel “1849”, I discovered I opened a whole can of worms for myself. I cannot stop. There are still so many stories to be told. I am writing my second novel now, a sequel of "1849".

---

More: 《一八四九 日出日落 ——一片茶葉改變了中英兩大帝國的命運》簡介

---

Copyright@ 2016.8.2 明報副刊 (網頁版)

小說家高峯之子甄子明 61歲延續父親寫作夢

【明報專訊】寫作,像把文字擲入字海,咚的一聲,沒平地一聲雷,就永沉水底。上世紀五十年代,新派武俠小說興起,除金庸、梁羽生外尚有不少寫作武俠文學的作家,如高峯、風雨樓主、江一明等。幾許風雨,武俠文壇沉寂,多少作品在年月中被湮沒,再難復見。商人甄子明說,那是父輩的故事了。他的書櫃放了父親的小說複印本,視如珍寶。

甄子明的父親原名甄名誠,筆名高峯,二戰時期於內地學成,戰後搬到香港,當了好陣子數學教師,便轉行當小說家。他看見父親半生埋首文學,對文字亦生好感,卻沒有選擇從文,反而踏上工程之路,成為首批到內地作基建的香港工程師,耳順之年現任上市公司主席,仍然毋忘前人握筆遺姿,忙碌中也花了四年翻查史書,創作有關鴉片戰爭的歷史小說。

甫抵甄子明家門口,便聽到他在陽台上談電話,正在交代下屬該打電話給誰,和什麼人傾談,如何計劃,指揮若定。聽到開門聲,傭人知會了一下,他從陽台中轉出來,身上仍套着一件圓領汗衫與睡褲,見到記者,進房又換上一套西裝,握過手後,傭人馬上端出紅茶與曲奇。比起想像中的中港商人,甄子明更像大學教授,一臉儒雅,喝了口茶,便在書櫃中掏出許多外國文學,說近來正系統地讀英國文學。

我的正式教育——金庸小說

他的故事又是另一個舊時代的風景。九十年代他北上工作時,中國仍然百廢待興。回憶小時候,甄子明的家全屋都是書,父親天天伏案寫作,家中中西名著俱全,但他仍然獨愛中國詩詞與各路武俠小說。最早影響他的作家,一是父親與金庸,二便是中國歷史小說作家二月河。歷史與武俠小說中的大國河山,春花秋月,使他對中國這個地方產生情義結,工程學院畢業後,他便一直等待機會,想到內地看看。

九十年代,不少國企想到香港上市,有國企公司向他招手,內地老闆放下國企一套,跟他說在香港工作就想用香港方式辦事,請他加入公司,甄子明欣然接受。「記得剛畢業出來做建築很辛勞,那時沒有環保條例,一個月只有兩個星期天可以休息,平日天天上班,又老是加班,試過半夜三點落工地工作。」他落地盤,一樣蹲在地下休息,天南地北與工人無所不談,文雅書生總算真的認識江湖。

「為什麼當年選讀工程?」他聽到記者問,半支着頭,說其實自己現在也仍在問自己這條問題,半晌才道﹕「那個年代直到現在,社會仍是叫年輕人走實際的路,讀實際的學科。但如果這把年紀讓我重新再選擇,會不會仍是工程,我也不肯定。」他和父親一樣,擅長理科又喜歡文史,父親甄名誠畢業於數學系,甄子明則在工程學院出身。

談着,他指着書櫃上全套的金庸小說,說那就是他的正式教育,他對世界,或是中國的認識都是在它們之中得到。之後又打開旅美中國史學家何炳棣的書《讀史閱世六十年》,史學家在書中附以私人信函與學術界的密件,仔細述說了自身六十年讀史閱世的心得,反映了當時留學一輩飄洋過海追求知識的學思態度。「歷史是我的最愛。這本書受了物理學家楊振寧《讀書教學四十年》所啟發而寫,但何炳棣寫得比較有趣。因為楊振寧的物理和大部分人關係不大,何炳棣的歷史卻與任何人都息息相關,顯得尤其親切。我一直跟自己的子女說,歷史是眾多科目中最重要的。一個人不認識過去便不足以了解現在。今年是文化大革命五十周年,許多報道重新分析文革如何影響現在,其實不要說到五十年那麼遠,即便是去年發生的事也會影響現在。如果一個讀史的人說讀歷史是讀過去的事,那他根本沒有讀通歷史。」客廳上,放了一個健美黝黑的少女畢業照,那便是甄子明的女兒,她與何炳棣一樣,都是美國哥倫比亞大學的歷史系學生。

「歷史是我的最愛」

甄子明的書房放了各樣的陶製高盤,其中一個盤子放了毛筆與墨水。書櫃最頂是《楚辭》,張愛玲的《金鎖記》、《對照記》、《半生緣》,還有李白詩選、宋詞賞析與《林徽因傳》。知道記者喜歡林徽因,他點頭,說林的確是難得文武俱全的女子,說完徑自從放卷軸的瓦筒內拿出一卷字畫,掛在書櫃上,解下繩子,揚開,坐下便讀卷中的詩﹕「我說你是人間的四月天;笑音點亮了四面風;輕靈,在春的光艷中交舞着變。你是四月早天裏的雲煙,黃昏吹着風的軟……」念的正是《你是人間的四月天》,他的心中有一潭柔情似水。

再談到張愛玲,他說到炎櫻,那膚色黝黑的印度女子。又說到張愛玲的散文,文中如何描述了戰時香港的情况,大學裏的洋教授走的走,留下來當兵,最後有了怎樣的結果……說到戰爭,他從書櫃底找出了一本像年報一樣的相集,那是義勇軍(The Hong Kong Volunteers,HKV)的紀念冊。原來,他曾經在那「當」過兵。

八十年代,他加入了和平時代的「軍隊」。適逢中國剛改革開始,經濟成果尚未浮現,內地仍然窮得緊要,人們三餐艱難,視香港如同天堂,偷渡到香港的事還有發生,甄子明的任務就是在邊界捉非法入境者,那時他才二十多歲。「當時警察主要在邊界站崗,由於我們是機動的,於是由我們去捉。」說到年輕往事,他格外感慨﹕「在我手上曾死過一個人,不是我直接殺死的,而是因為守衛嚴密,那個非法入境者上不到岸,在我眼前淹死了。」當兵的經歷使他想像到戰爭的可怕,從此明白高高在上的人做了決定,下面的人喜不喜歡,也要硬行,叫前線的士兵不得不面對生死——「天下的戰爭都一樣,人命忽成草芥,沒有道理可言。」他說。

重現鴉片戰爭後中國興衰

約十年前,子女皆學有所成,他方停下來,回想父親著書的背影和自己從小萌芽的寫作欲望。如此匆匆半生,沒有安靜下來過,他寫作的欲望早已育成大樹,五十一歲,他才在樹蔭下定決心,埋首港大圖書館蒐證、研究,最終寫成幾萬字的歷史小說《一八四九日出日落—— 一片茶葉改變了中英兩大帝國的命運》,以文學方式重現一次鴉片戰爭後中國的興衰故事。

很難想像面前這位一臉斯文、不擅言語,又熱愛文史的人,走進內地談生意時燈紅酒綠的景色。甄子明笑說,其實他辦公室常備一盒紙巾,給員工被他鬧哭時用的,廿幾年的從商經驗,使他學會了見什麼人講什麼話。「在內地做生意,首先要懂得『交朋友』,中國文化裏頭『信任』很重要,中國整個社會制度都建基於人和人之間默認的關係之中,有些關係有無合約都好,分別並不大。」

「香港人之所以常常覺得和內地人做生意,信不過對方、易被騙,其實是因為兩者沒有建立起關係。我們慣了西方那套,合約簽了,交情別談。但我訓練同事到中國工作第一件事就是教他們交朋友,尤其和官交朋友。」他是首位把香港地鐵加物業的房地產模式帶到中國的工程師,他說已經無悔。但問下去,他說沒打算退休,花現在才開得燦爛。他閒時寫書,上下班的時間自由調節,上星期公司才剛公布了新的發展方向。他天天起牀都開心,睡着也笑着。

I wanted to paint a different (and possibly untold) picture of China and Britain after the Opium War, the story of which has seldom been revealed.